As is our custom, we'll let Paul tell us a bit about himself:

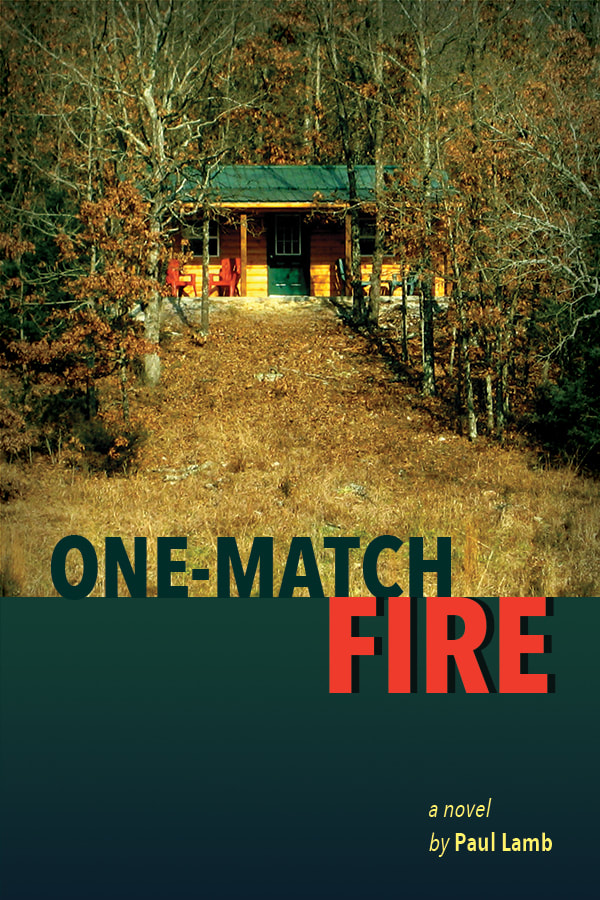

I have a cabin in Missouri, at the edge of the Ozark Mountains. The cabin waits most of two hours away from my home in suburban Kansas City, and while I visit every chance I can, it is an undertaking to get there, engage in chores or foolishness, and then get home in a single day.

I can’t remember when the seed was planted to have a cabin in a forest, but I suspect it was during my summer nights at Scout camp, when I was first serenaded by whippoorwills.

When the cabin became a reality, it dismayed some of my friends. One in particular was baffled by how I could profit from rocky, scrub forest too thick to plow and too thin to timber. I told him I intended to write at my cabin. “You can’t pay your bills with writing, Thoreau,” he had scoffed. This exchange made it into my first novel.

The irony is that I don’t write there. The setting seems ideal, doesn’t it? A one-room cabin with a shady porch overlooking a sparkling lake, at the end of a road no one needs to come down, deep in a trackless forest. The only sounds that intrude are the occasional lowing of cattle from the ranch to the east or maybe a distant chainsaw. I have a chair and a table and pencils and notebooks there. I have uninterrupted solitude. I have everything a writer needs, and yet I cannot write at my cabin.

I’ve tried. Repeatedly. I’ve schlepped out there many times with my laptop and back-up battery and installed myself at my table. Notes at hand. Rested and ready. And all I feel is a desire to go outside, into the forest, down to the lake, along the paths. I want to see what bird is calling, whose shadow is floating across the ground, what I heard scampering through the leaf litter. I want to feel the sun on my skin or listen to the rain on the roof. Stare into the orange flames of a campfire. I want to throw a line in the water or watch for a beaver emerging from the lodge across the lake.

In short, when I’m there I want to do all these things that keep me from entering the fictional universe where my characters go about their lives and let me observe them.

Instead, I write at home. I’ve been doing this for a long time, so I call it a win. Originally, I was writing freelanced feature articles for newspapers and magazines. Sometimes it paid, but mostly it paid in bylines. I developed a rapport with several editors who regularly took my work, but they’d move on, and the new editors brought their own writers. My work grew unfocused; I would write about anything that would get me published. But during this feature work I was also quietly writing fiction, practicing my craft, and wondering when I would dare try submitting a story.

At a writers conference, the editor of a literary journal turned to me and, completely unbidden, asked what kind of writing I did. I told him about a story I had recently finished full of introspection and regret. He said to send it along, so I did. And he took it. I had finally become a published fiction writer.

About this time I had completed a master’s degree in English and Writing from the University of Missouri at Kansas City. I had pursued this purely as an indulgence for myself, still reeling from my misguided and soulless undergrad degree in business administration. I didn’t get the master’s to make myself more employable but to immerse myself in what I liked best and what two prescient high school English teachers had told me I should aspire to. I’m glad I did.

I continued to write features, and get them published, but the personal satisfaction that came from fiction grew, and I eventually abandoned feature work altogether. In my short stories I controlled the universe. I could write about whatever I wanted, go in any direction I wanted, and reach my own conclusions.

Most of my published fiction is what would be considered literary. Character focused, with human emotions at stake. I’ve dabbled a little in very light fantasy and even some speculative stuff, but I’ll leave that to the professionals and continue to write what seems to be my calling.

Among these stories was one I wrote about a little cabin in the Ozarks. It was supposed to be a one-off, a sort of guide for what my children might do with my cabin when I was gone. I thought the story worked well – it was eventually published – and I certainly knew the setting thoroughly. Then I thought maybe I could write another story about the cabin. That one worked well too and was also published. These stories brought a momentum with them, and soon I had a half dozen set at the cabin or about the characters connected to it. I began to wonder if I had the beginnings of a story cycle, though a friend told me that no, it was a novel. That novel became One-Match Fire.

I’m retired now from being a wage slave in the vulgar business world where I had worked to pay my bills but had never sought a career. My children are grown and flown, leading fulfilling lives. I am free to pursue writing my stories as much as I want, and so I do.

Welcome, Paul!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed